BEYOND TIMES AND SPACE

FORMAL COMPASS, FABRIC OF EMOTIONS, IDENTITY ROOTS: FOR ALL LIFE THE ARTIST-JOURNALIST HAS SEARCHED FOR ORIENTATION IN THE ANCIENT PEOPLE. IT IS SHOWN BY A VENETIAN EXHIBITION THAT OFFERS CANVAS AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS

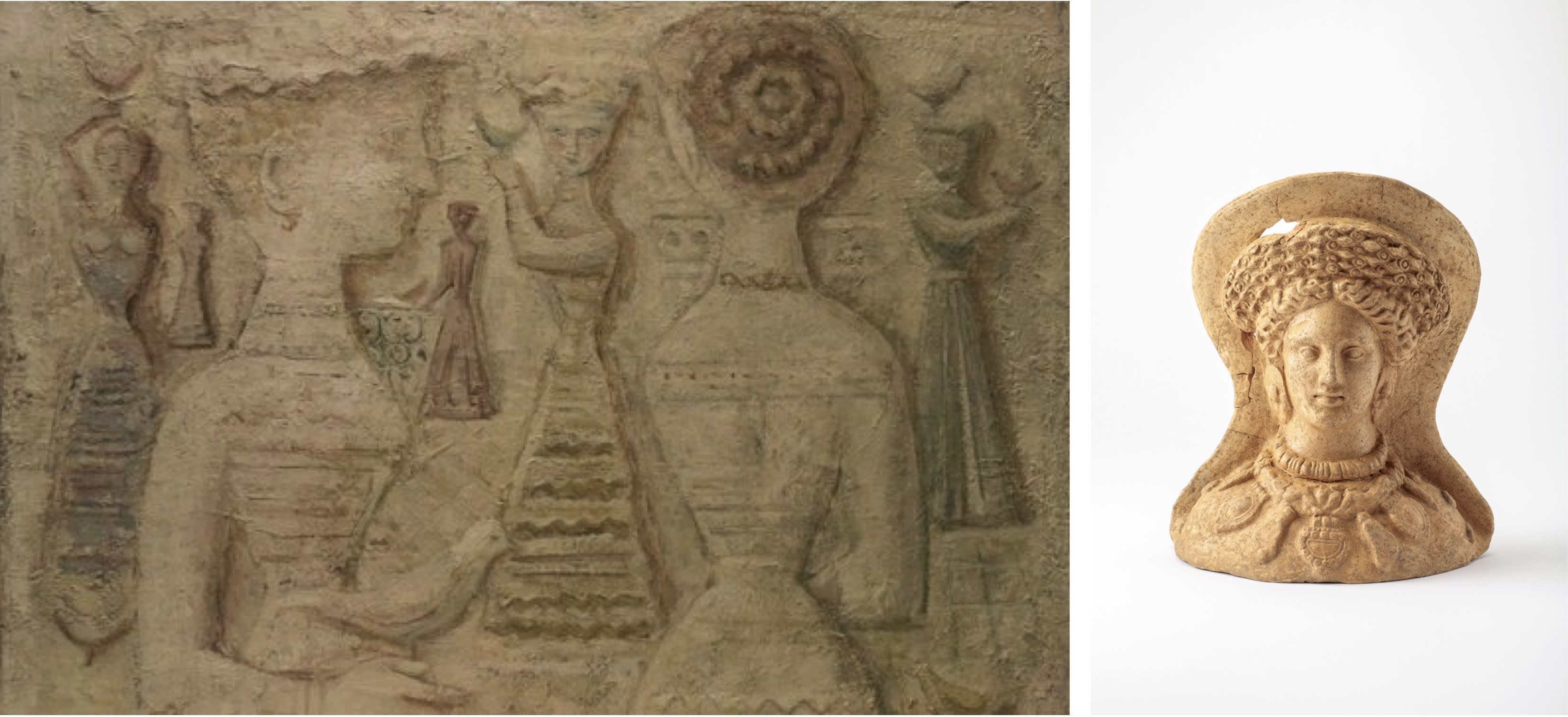

Massimo Campigli, Women and birds (1944, olio su tela); Woman's votive bust (III century. a. C., terracotta orange-red with pigments traces, Cerveteri, Necropoli della Banditaccia).

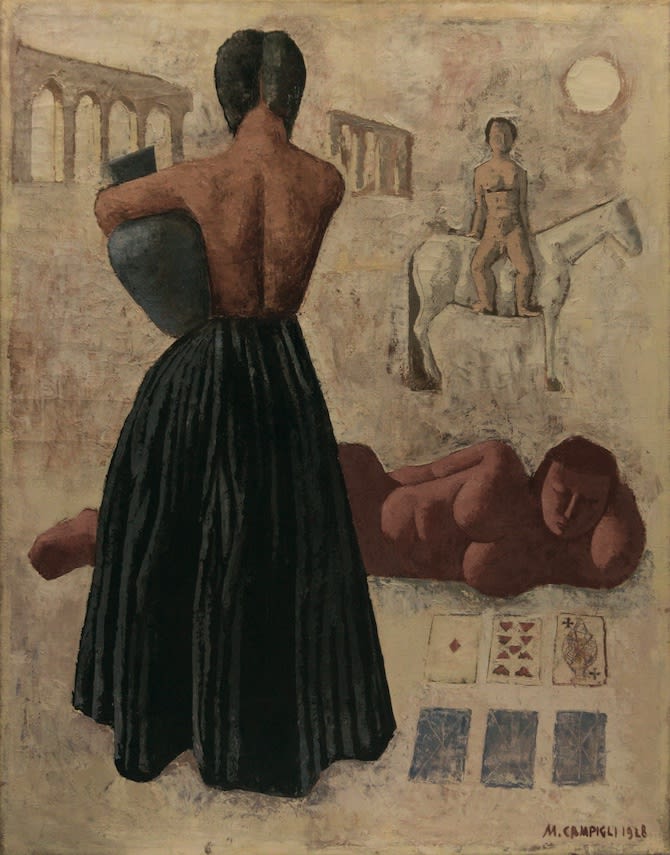

Massimo Campigli, Gypsies (1928, olio su tela).

Thus, passing the majestic staircase of Palazzo Franchetti, in the first room we find ourselves in front of a sarcophagus and a painting that represent the synthesis of an epiphany and this exhibition: the painting is titled “Gypsies”, it is from 1928: two female figures (one from behind, with bare backs and an amphora in hand) are immersed in a landscape where the remains of the Roman aqueduct declare a sacred homage to history. The painting takes on a further value, due to the enigmatic presence of a man sitting on horseback and a woman lying down looking at the cards of a solitaire game. The reclining figure of the painting dialogues with the covering of an Etruscan sarcophagus in which a woman seems to be addressing the painting: a game of references, quotations, cultural ties in which Campigli's love for the origins of history is evident, indeed of all the stories. Starting with him.

So let's start from his private life, at times adventurous, certainly full of passion and torments: Massimo Campigli is the pseudonym of Max Ihlenfeldt, born in Berlin on 4 July 1895. His parents are German and his mother, Anna Paolina Luisa Ihlenfeldt, becomes pregnant at eighteen. The girl comes from an upper middle-class family: at that time a single mother represented a scandal, so she entrusts the child to the care of her maternal grandmother who lives in Settignano, near Fìrenze, where the young woman and the child move.

The entrance of the exhibition.

In the eyes of the world, Anna Paolina, the mother, was everyone's aunt. Little Massimo, after his mother's marriage to Giuseppe Bennet, a British representative of colors, is taken to Florence and then to Milan. Only at the age of 15, casually reading a document, does he discover that "Aunt Anna" is actually his mother. The following year his stepfather dies and Massimo remains with his mother and the two sisters born of the marriage. It will be in Milan that a very young Campigli discovers painting. Then, not even twenty, journalism. The First World War is looming and Campigli, in the hope of having an Italian passport, enlisted as a volunteer. He fights on the Karst, is taken prisoner, escapes, reaches Moscow, witnesses the October Revolution, lands in London. Only in 1918, when he returned to Milan, was he granted Italian citizenship for military value. At this point he is finally summoned to the Corriere della Sera, which sends him the following year to be a correspondent in Paris. He is a painter by day and a journalist by night. And viceversa. He lives in Montparnasse, he frequents the Café Dôme. And with Giorgio de Chirico, Mario Tozzi, Gino Severini, Filippo De Pisis, Renato Paresce and Alberto Savinio he forms the group called «The Seven of Paris». From all this whirlwind of dates, places and events, there is a lively tension, a need for legitimacy in a constant search for identity: both on the level of political citizenship, and in that symbolic gesture of emotional refusal on the part of a mother. In fact, entrusted to another woman. From a psychoanalytic point of view, origins could be said to be taboo. «How much I look like my paintings!». He writes one day. «In psychoanalysis I have looked for and found a way to put some system into my 'madness'». The exhibition investigates this relationship between Campigli and the female universe - women painted as hourglasses, elegant, jeweled figures (an extraordinary portrait of his second wife, Giuditta), a world that made him suffered but also welcomed him. The second point, on which the exhibition investigates, is precisely the fascination for the Etruscans (highlighted through frescoes, jewels, amphorae, painted plates, votive heads), symbols of a primeval identity of his being "Italian" and in which he is immersed, recognizing himself, as a man recognizes his vital source: «A Villa Giulia I met something that was already in me».

But then he is also capable of elaborating a critique of his own work: «My painting has major fundamental defects: there is too much museum, no life, it is inhuman and the colors are dull, chalky, fake fresco, there is a geometry in delay on the times, is completely out of the movements etc.». And with a great sign of intellectual honesty, and as a free man who went through the twentieth century out of fashion, he adds: «Yet it exists and resists, it is not neglected, it must have a certain reason to be. He saves himself for a certain particular way of being wrong. It is not cheap».