THE ETRUSCAN INFLUENCE ON THE WORK OF AN ITALIAN MASTER OF THE '900

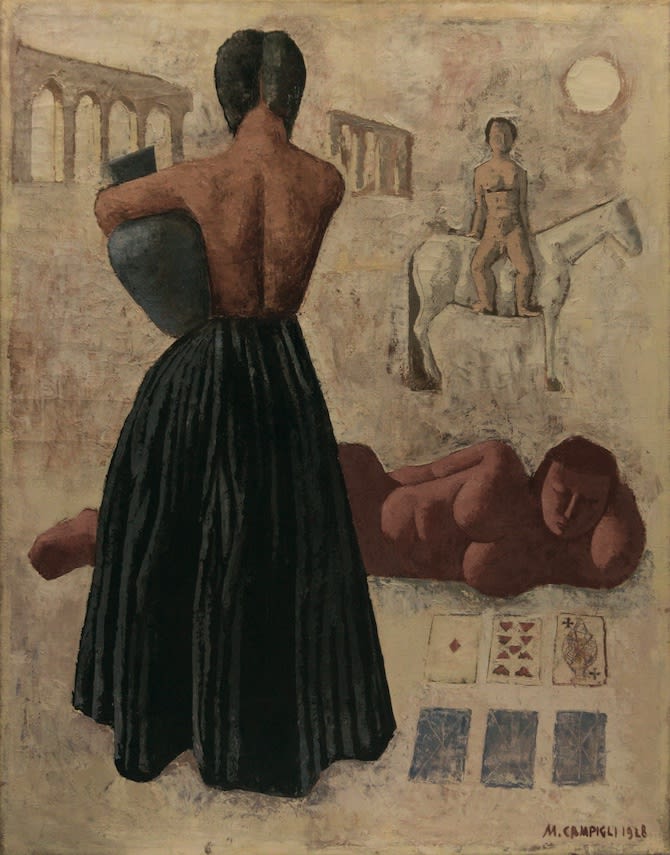

Gli zingari, 1928, oil on canvas, cm 96x76. Augusto and Francesca Giovanardi Collection, Milan

An exhibition on Massimo Campigli (Berlin, 1895 - Saint-Tropez, 1971) as it had never been attempted: with thirty-five paintings and about fifty Etruscan finds, Massimo Campigli: a pagan happiness, open at Palazzo Franchetti in Venice from 22 May to 30 September, demonstrates all the influence of Etruscan terracottas on his painting. On the fiftieth anniversary of the artist's death, it proposes a convincing interpretation of him.

Massimo Campigli, Donne con l'ombrellino, 1940, oil on canvas, cm 100x81. Augusto and Francesca Giovanardi Collection, Milan.

Female head antefissa, second half of IV century (Montaltodi Castro, Fondazione Vulci).

SMILING HUMANITY.

1928 was crucial for Massimo Campigli, who the year before had decided, among a thousand doubts, to leave the activity of journalist to devote himself to painting. In the summer, from Paris where he lived, he goes to Florence with his wife and soon and then to Rome where, at the Museum of Villa Giulia, he is moved by the vision of Etruscan art. «I knew Etruscan art like everyone else. But only in 1928 was I ready to receive the coup de foudre. I recognized myself in the Etruscans. I loved this small, smiling humanity that makes one smile. A pagan happiness entered my paintings».

MYSTERY.

Gli Zingari ("The Gypsies"), which dates back to 1928, is a work linked to the artist's previous career and the women are still monumental as in the first paintings inspired by Picasso. As always, in Campigli, everything expresses a sense of mystery: you don't know whether those palmists and water carriers are our contemporaries or come from a very remote past.

Mssimo Campigli, Donne e uccelli, 1944, oil on canvas, cm 72x92.

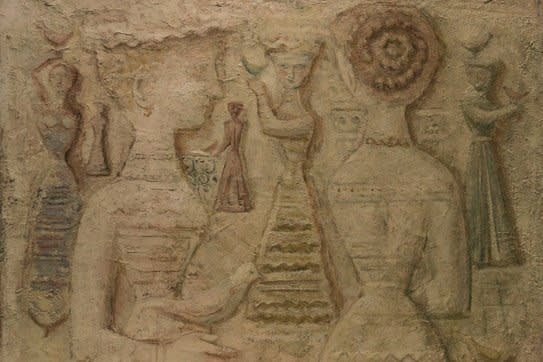

Women, for him, are an enigma (even concretely: the artist was the son of a single mother who had had to pretend to be his aunt to save appearances). Immediately after 1928, however, the Etruscan inspiration becomes more evident and the female faces appear more and more similar to ancient Tuscia terracottas. Their geometric bodies, stylized as in an hourglass, the rectangular hairstyles, the rhythmically decorated clothes recall the fixtures of temples or the women lying on Etruscan sarcophagi.

Even the colors, the ocher, the calcined whites, the pinks, recall that distant world. Campigli thus demonstrates what Shaw said: the past is always present. The only thing that's really old is this morning's newspaper.